Samantha Irby on complaining:

Complaining is like spreading lotion on dry skin, and 2017 has been the ashiest year in recent memory. There is more than ever to complain about and also more reason than ever to believe your complaints might actually do something.

Resist the urge to unload your economic anxieties on the dry cleaner and instead make a video about it or write one of those long statuses everyone is just going to scroll past anyway. Then, when you’re all wrung out, when you feel that you don’t have a single complaint left, dredge up a few more and call your member of Congress. That way you can at least try to turn your seething rage into affordable health care.

Fucking A.

I am so fucking sick of hearing people complain. In my office, by my unofficial count, the people I work with spend 99% of their time complaining about something (I’m confident I’d find the same percentage in every workplace).

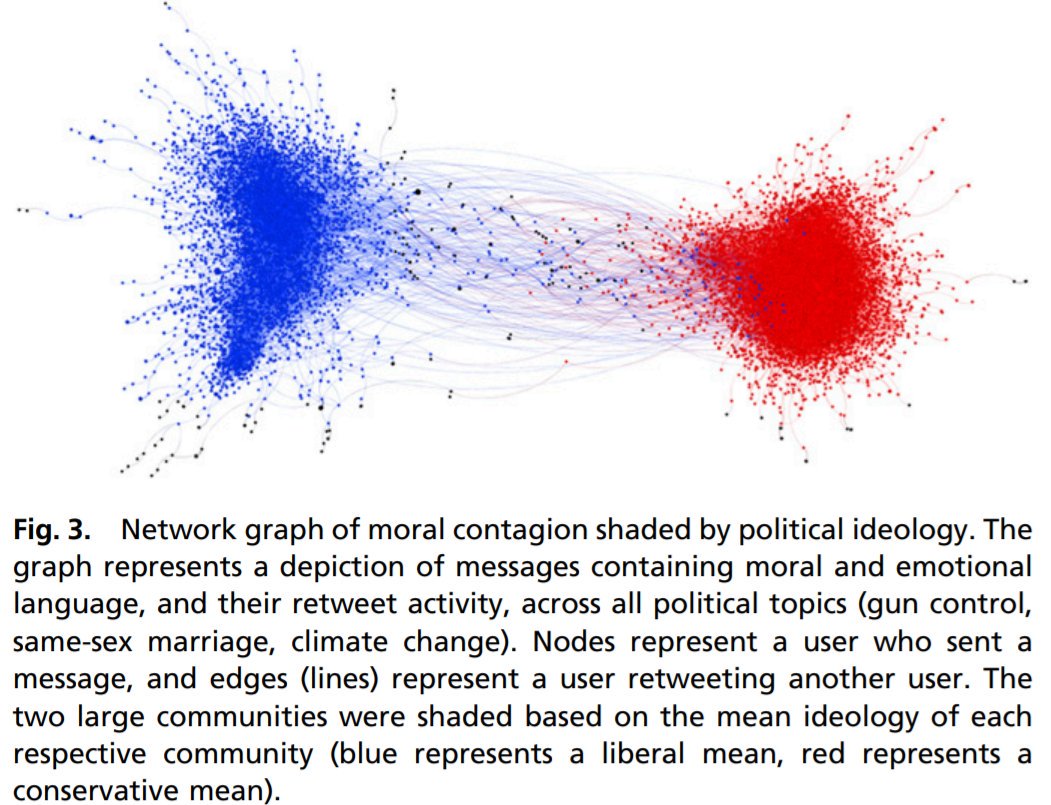

But it’s not just people at work, it’s everyone. I’ve unfollowed people on Twitter and cut back on how frequently I use the service because, as Irby points out, “2017 has been the ashiest year in recent memory.”

A few years ago I made a quote by James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem my mantra: The best way to complain is to make things.

We don’t all have the luxury of being a paid to complain like Bill Burr, but that doesn’t mean you don’t have the power within you to transform a complaint into something else.

You might be saying to yourself, “But Mike, you’re complaining right now,” and you’d be wrong. This is a blog post built from complaints that were floating around in my brain. It might not be a music, or a New Yorker cartoon, but it’s no longer a complaint.

You actively sought out my silly little website and chose to read this blog post.